The DeGive Dulcimer

I am always on the lookout for good wood. Construction sites are rarely the source of this. However the architecture firm for which I work is undertaking the renovation of a home in historic Ansley Park which was built in 1911 and has some excellent tight, straight grain to its pine studs. I was granted my pick of the framing which was considered too 'structurally compromised' to remain in the remodeled house. It is these very defects that ultimatly made the instrument I created from the wood most compelling.

I have compiled both the instrumnet construction and house history illustrated below into "The DeGive Dulcimer Story" which can be downloaded here.

Known by the locals as either the DeGive House or the Hunt House, depending on which family you knew, the place has a colorful past as I found out in my several weeks of research, mainly directed and finding original drawings or even a reliable early photograph so we could see what the house looked like to the first owners, because it comes to us in a very poor state of health with many haphazard and stylistically out-of-character additions.

This is the earliest photo I found of the house, at the Emory University Department of Archeology slide library. It is undated, however I was later to find out it was photographed from a book entitled "Georgia Homes and Landmarks", published in 1929. Another book, "Georgia Homes and Notable Georgians", published by M.M. and A.H. Howard in 1941, has a similar image with the following copy:

"Atlanta is a city of beautiful homes, and one of the loveliest is that of Mr. and Mrs. Henry L. de Give. The house is set well back from the street, beautifully framed by luxurious oak trees. The architecture of the house is of English origin, using red tapestry brick, a light plaster, and deep brown wood to provide a contrast in color. The brick walls and terraces are picturesquely covered with English Ivy. Ivy is also the theme for a delightfully shady garden on the north side of the house. In this garden the ivy is supplemented by many shrubs, among which are rhododendrons, mountain laurel, and boxwood. The ivy garden is completely enclosed by an artistic wrought iron fence with lace-like, hand wrought iron gates. Beyond this is the rose garden which abounds with many varieties of beautiful roses.

The de Give family has been outstanding in Atlanta since the days of the Civil War, and has contributed widely to the building and advancement of the city.

The patriarch of the family, Laurent de Give, was sent by King Leopold of Belgium to this country before the Civil War to establish trade relations between the southern states and Belgium. He served as Counsel for fifty years and was decorated four times by his monarch. Mr. de Give never relinquished his Belgium citizenship. At his death in 1910, his son Henry was appointed Consul, and has held this position since that time.

Mr. and Mrs. Henry L de Give have a daughter and four sons: Mrs. Marshall

J. Wellborn, Henry, Laurent, Paul, and Louis. Henry and Paul now reside

in New York City."

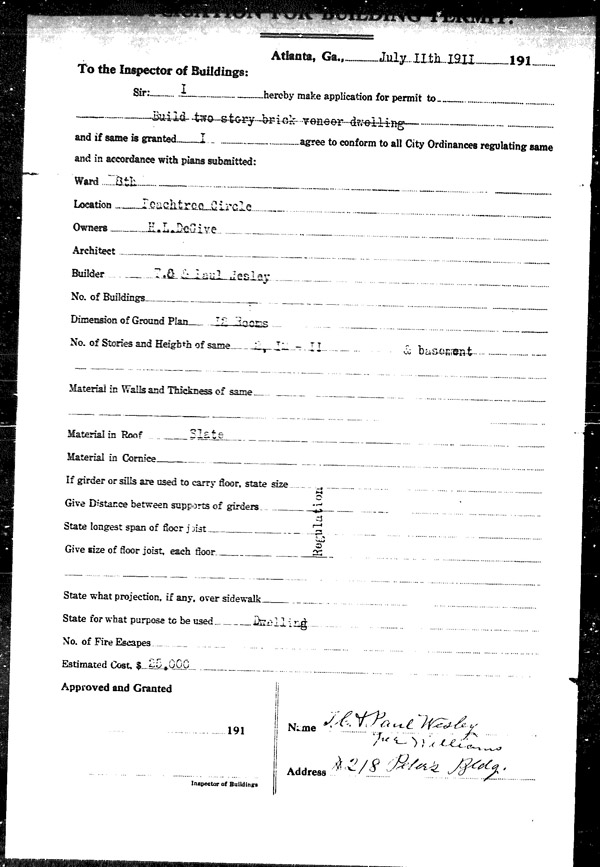

This is the original building permit, showing the builder, but not the architect. In conceiving the renovation design, I toiled over who the architect - if there was one - might have been. Mysteriously, during selective demolition we found the tattered remains of blueprints for Hentz Adler & Schutze Architect's design for the Emily Winship Woodruff Maternity Center at Craford Long Hospital, opened 1945. There is a connection between the second owner of the house and this firm which I will not go into here.

The house was purchased in 1961 from the DeGive estate by Frania Tye Lee (Hunt), notable for being once married to Texas oil tycoon H.L Hunt as well as being a previous owner of Atlanta’s “Flowerland Estate”, where after many years of using the property as a private residence established D’Youville Academy for Girls there. The most heart-rending detail I cam across concerns Frania's daughter, who as a leading Atlanta thespian of the time was among those who perished in the 'Orly Disaster' which deprived Atlanta of it's leading cultural and philanthropic luminaries on 3 June 1962. The house was a center of social activity in Atlanta during Farina's early ownership and she hosted the 'going away party' in the house for those participating in the month-long cultural foray to Europe in the week before departure. Her grandson was left orphaned in her care and grew up in the house with his grandmother, who passed away in 2002.

The house as it looks now (Fall 2008), on the first day of shell demolition, with the sleeping porch having been covered over sometime in the 1970's when the house was converted to apartments. This view most strikingly conveys, I feel, that the 'Tudor treatment' of the second level is not appropriate for the house massing or first level treatment. But I digress. This is supposed to be about lutherie.

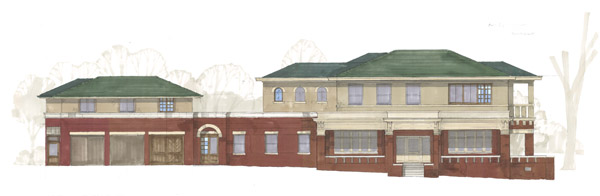

Two rendered view of the remodeled concept. Drawing from the more beaux-arts aspects of the original design: The polychrome brickwork, symmetry, heavy entablature and attics, etc. The imperative was keeping the addition to the rear and fixing the architectural "mistakes" of previous renovations while retaining the strongest features of the original design.

+++++

I am naming this project after the DeGive family, the first family to inhabit the house, from 1911 to the end of the 1950's. I've decided to make a lap dulcimer out of it because, besides being a simple instrument that is more likely to be successful made entirely out of pine, it is an Appalachian instrument that at the time period this house was built was just coming to the consciousness of the urban public. In fact I am going to use as my pattern an instrument which was collected by the Smithsonian at this time. It would have been quite possible that the DeGive children would have had mandolin, banjo, and even dulcimer as part of their musical amusement.

Here are some shots of preparing the wood. First all nails and bits of whatever have to be removed. This nail is driven in at such an angle that a plug cutter couldn't get around it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Not a 1911 nail

.jpg)

In several places there is writing in pencil in a florid script which likely is of the original builder

.jpg)

The piece with the most quartersawn cut is selected, planed and sliced into the side wood.

Here one of the sides of the instrument is planed and trued on its edges. It includes a 3/4" conduit hole and holes made by nails and insects.

The fingerboard is riddled with nail holes from plaster lath. The sides have a variety of distress, from hammer blows to conduit holes. Shown also is the pegbox pattern I will use.

The pegbox is complete. The center of the scroll is a conduit hole hey that rhymes.

The sides of this instrument are thicker than usual to counter the structural liabilities of the various defects. Usually my dulcimer sides are 2mm thick, these are twice that thickness. So instead of dry bending the sides on my usual electric bending iron I'm having to use a propane heated pipe and pre-wet the sides.

One of the sides is bent

The sides are bent and glued to the head and tail blocks. Vise as weight. Ryobi product placement.

Sides are glued to back

Due to all of the jagged penetrations, I am taking the precaution of installing splines on each side of each opening to preclude future splitting. Basically, the inside of the instrument will be riddled with these strips.

Such as this location.

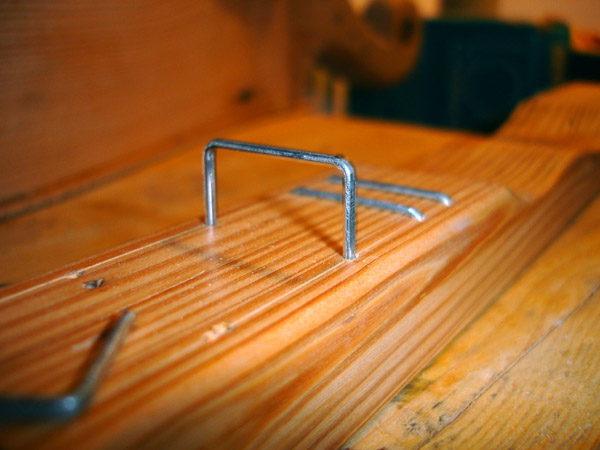

The frets of the earliest dulcimers were often fence post staples or bent nails. Here I am using a 1" wide industrial staple which is very similar to an early packing crate staple. In some cases a guide hole lined up with an old plaster lath nail hole.

After the frets are in place the fretboard could be glued to the top. The old plaster lath nail holes make an interesting background pattern.

Detail of fretboard glueup.

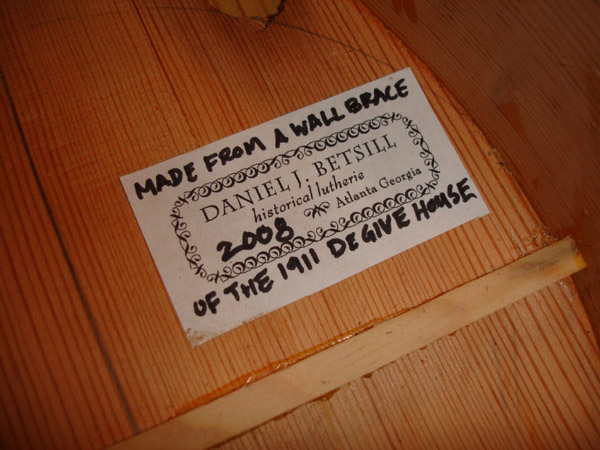

Before gluing the top on, don't forget the label. I almost did.

Top being attached. My violin-size spool clamps don't fit, so I'm doing it the old fashioned way.

The top is attached and the edges are being trimmed. A hallmark detail of the earliest dulcimers is the presence of 'overlapping edges' as opposed to flush edges that are used on most modern instruments. This detail is reminiscent of the fiddle, which was probably the most familiar 'store bought' instrument to the rural makers. The gap visible between the end of the fingerboard and the end block is for the insertion of a string holder. Since I am making all the parts of the instrument from pine, this piece will have to be firmly rooted.

The string holder being glued up. Gorilla glue.

The pegs will have a nice round, basic shape and be as thick as my reamer will allow. Although I've seen alot of rural, early dulcimers with pine friction pegs (usually with square heads because they were carved by hand) it is not a good choice because it is far too soft a wood. I am going through the pains of ensuring that every single piece of the instrument (except the frets!) is made out of that one pine stud. The pegs of this instrument will have to be well soaped to reduce binding and twisting of the shaft.

.jpg)

Sides are trimmed. I'm taking advantage of a nice sunny day to do the final sanding and finish application outdoors. I will also let the finish cure in the sun today. Here the instrument is only lacking the nut and bridge pieces, which I do not want to be finished for acoustical reasons. Otherwise, the whole instrument is getting a raw linseed oil and turpentine cut finish rubbed in. Two coats. This was a traditional finish for rural woodworkers.

.jpg)

++++++

Completed images

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

++++++

Another "DeGive" Dulcimer in the works. Showing here the raw material, the studs of the 1911 DeGive House in Ansley Park, complete with my marker tag to the contractor designating which pieces I wanted salvaged. The sides and back pieces are sawn and planed, the scroll and endblock are complete and the fingerboard is planed to size, with a few objects of ejectus.

The frets for the first instrument were of the largest packing staple I could find at my local hardware store. They weren't quite wide enough to play all three strings easily. So I'm pounding them out for this instrument to make them wider.

Like many of the old makers, I am leaving my scribe marks: the lines I made to position the drill holes for the frets. When I pick up an old instrument, I like seeing the evidence of how the maker worked.

"Allus-ago I yearned to view the sea./ Maw had a sight of old song-ballads for/ To sing us young-uns, picking out the tunes/ On her old dulcimore. The one I liked/ Was that that told about the Old Salt Sea,/ And Ships A-Sail, and wonders of the deep"

-Ann Cobb from A Mountain Seaman

Dulcimer over the fireboard, hanging sence allus-ago,/ Strangers are wishful to buy you, and make of your music a show;/ Not while the selling a heart for a gold-piece is reconed a sin,/ Not while the word of old Enoch still stands as a law for his kin.

-Ann Cobb from Dulcimer Over the Fireboard